Share James Grauerholz's obituary with others.

Invite friends and family to read the obituary and add memories.

Stay updated

We'll notify you when service details or new memories are added.

You're now following this obituary

We'll email you when there are updates.

Please select what you would like included for printing:

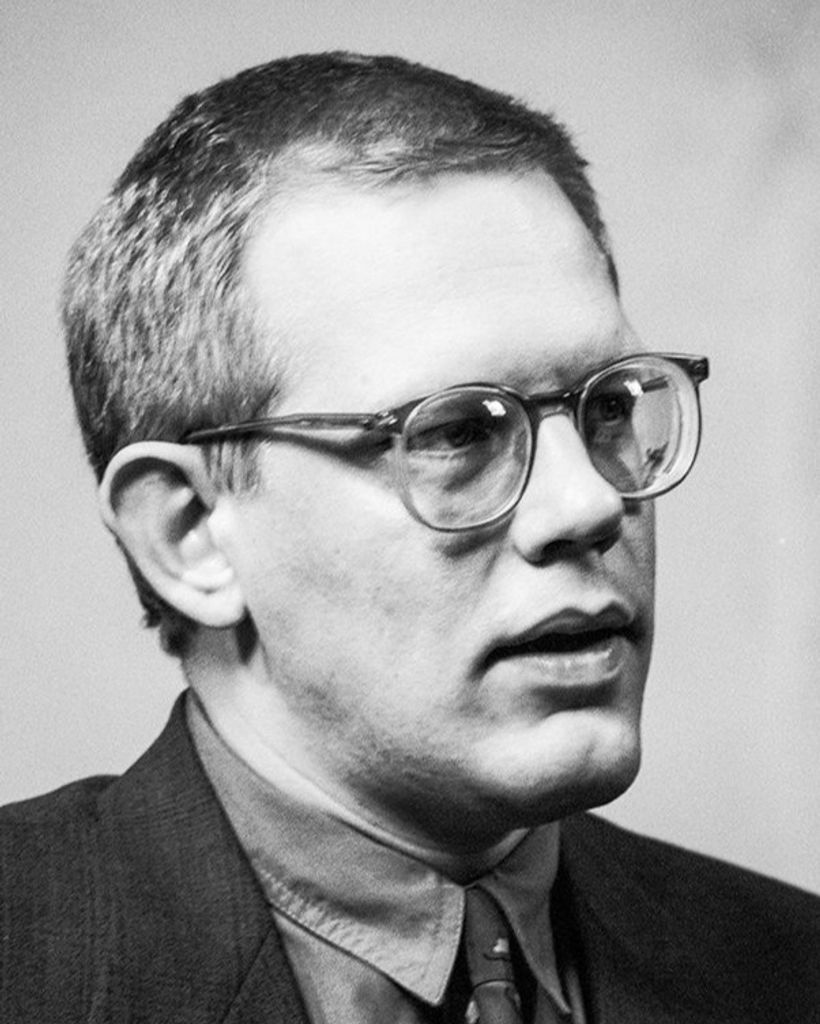

James Grauerholz

December 14, 1952 — January 1, 2026

Share James Grauerholz's obituary with others.

Invite friends and family to read the obituary and add memories.

Stay updated

We'll notify you when service details or new memories are added.

You're now following this obituary

We'll email you when there are updates.

Please select what you would like included for printing:

James Grauerholz, who died on New Year’s Day after a long illness aged 73, was a writer, scholar, editor, musician, and from 1974 the companion and later adopted son of the American writer William S. Burroughs for 23 years until his death. For another 28 years, James was the executor of Burroughs’ estate and guardian of his legacy.

The only child of Selda Paulk, a singer, stage performer, and costume collector, and Alvin (Fritz) Grauerholz, a lawyer and local politician, James was born on 14 December 1952 in Coffeyville, Kansas. During a troubled childhood, which included a spell in a children’s home, his sexuality and intellectual ambitions led James to find escape in literature and at age 13 he first encountered Burroughs’ notorious landmark novel, Naked Lunch, which was to shape his destiny.

After majoring in Oriental philosophy at the University of Kansas in Lawrence, James dropped out in 1973 and contacted Burroughs, then living in London. In February 1974, the tall (6’ 4”), blue-eyed, fair-haired, 21-year-old boy from Kansas, in tight Levi jeans and a cowboy-style hat, met Burroughs, who had moved to New York after living abroad for a quarter of a century. It would prove to be a turning point for both men, and, after a brief sexual affair, James began a lifetime of devotion to the writer. He also began living with his first serious boyfriends, Richard Elovich and then Ira Silverberg.

Burroughs gave James entry into a world away from Kansas, and James was exactly what Burroughs needed: someone with an intuitive affinity forhis work, but who had the smarts the 60-year-old writer signally lacked. Acting as his secretary and impresario, James had the vision to help Burroughs reinvent himself and settle in a New York social scene of countercultural artists, musicians, and celebrities. James thoroughly professionalized Burroughs’ public readings and media appearances, enabling the writer to project himself through performances that brought his work to life and reached new audiences.

In the mid-1970s, James found Burroughs the “Bunker,” a converted YMCA space on the Bowery, which turned into an underground literary salon, captured on film by Howard Brookner in his 1983 documentary (rereleased in 2012). That film left an unflattering impression of James as arrogant and conceited, but it also reflected the self-confidence he needed to do his job and hold his own in such circles and with the likes of Allen Ginsberg and Brion Gysin. Because of Burroughs’ celebrity status and reputation as an addict, however, the New York scene soon spiralled out of control. James left, considered refocusing on his career as a musician, and moved back to his old university town of Lawrence.

Badly in need of James, Burroughs followed in 1981, returning to the Midwest of his own upbringing in St Louis. In 1983, Burroughs moved into a bungalow at 1927 Learnard that would be the writer’s home for the last 15 years of his life, helped by a community of friends and assistants, many of whom stayed on to support James, that included Tom Peschio, Wayne Propst, David Ohle, Jim McCrary, Steven Lowe, John Lee, Bob Richardson, Randy Renfro, Jason Eberth, James Thomblison, Phil Heying, Karl Gridley, José Férezand Yuri Zupancic. Although productive during the 1970s in New York, it would be in Lawrence, with James’ support, that Burroughs flourished in his American years, creating a series of major works of fiction, film projects, recording collaborations and, from the mid-1980s onwards, embarking on a career as a visual artist. As a business manager, James set up William Burroughs Communications and achieved a major book deal in 1985 that, for the first time, secured the writer’s finances.

Proud of being self-taught, James Grauerholz was a man of many hats. A fine musician with his band Tank Farm—an anthology of his solo songs was released in 2024—a brilliant researcher, talented editor, and gifted writer, he developed the skills needed to facilitate the many artistic projects of a globally influential cultural icon. Burroughs had always relied on others to both promote his work and help him edit it—and in James he found a collaborator able to stabilize the radically inventive but chaotic genius of Burroughs’ writing.

Burroughs died in 1997 at the age of 83, his longevity due in large part to James. As well as securing Burroughs’ local legacy in Lawrence, getting a creek renamed after the writer in 2004, James managed the estate. As when Burroughs was alive, so too after his death James went through times when the burden of his role outweighed the honour of it, if never the love he felt for Burroughs. Personal tragedy—including the suicide of his long-term boyfriend, Michael Emerton in 1992—combined with increasing physical and psychological issues as he aged, also took its toll.

And yet everyone who worked critically or creatively in the Burroughs field owed James an enormous debt. He supported innumerable researchers, and if some in later years experienced his resentment, many more experienced the extraordinary generosity with which he shared his unique expertise, a triumph of his better angels over his inner demons. Like the “Old Man” he loved, James was no saint, but he was a gentleman. Until his final year, he was a loyal friend to many, an erudite and amusing raconteur, both in person and via email. To have James’ full attention, to share his passions and even his frustrations, was a truly special feeling.

James had travelled the world but still retained his Midwestern roots. While his sexuality and politics set him apart from red state Kansas, he was proud to live in Lawrence, celebrating the Jayhawks’ basketball NCAA success in 2022, and his correspondence typically included some reference to his parents or extended family. He dutifully managed the legacies of both his parents, and remained close to his many cousins, including John, Susie, Tom, Tony and Mike Barelli, David, Brian and John Paulk, Martha Asasph, Karl and Kurt Schmidt and Greta Schmidt Perlberg. He will be missed by many. To quote one of Burroughs’ favourite poets, Edward Arlington Robinson: “We never know how much we learn / From those who never will return.”

Oliver Harris worked closely with James Grauerholz for 40 years and with his support has been the author and editor of over 20 books about or by Burroughs.

Guestbook

Visits: 2402

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the

Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Service map data © OpenStreetMap contributors